Miles Franklin and the Women Literary Journalists of Gonzo Ethnography

Immersing in low-wage labor brings to mind George Orwell's "Down and Out in Paris and London," yet there is a history of literary journalists that predate him and his work.

In the introduction to their anthology of Australian author Miles Franklin’s journalism, Jill Roe and Margaret Bettison describe her work as “topical writings.” Quoting the Macquarie Dictionary, Roe and Bettison define topical as: “‘matters of current or local interest.’ Such matters are inevitably diverse, and their treatment usually ephemeral. Thus ‘topical writings’ is a convenient umbrella term for a wide range of occasional pieces, mostly published in newspapers and magazines.” Within this umbrella definition Roe and Bettison include Franklin’s reviews, opinion writing, and the “occasional sketch and serial,” all of which are represented in the anthology. The mention of the sketch, however, teases that there are unrecognized works of literary journalism by Franklin blurred under the catchall “topical writings,” as the sketch is a historical indicator of the form exemplified by Stephen Crane’s writing. Accordingly, a closer read of the anthology reveals sketches that can be considered literary journalism: “San Francisco: A Fortnight After,” written when Franklin visited the earthquake- and fire-ravaged city en route to Chicago in 1906; and “Active Service Socks,” which describes the World War I camp in the Balkans where Franklin was stationed as a volunteer orderly.1 But most intriguing is “Letter From Melbourne,” published in the Australian periodical, the Bulletin, in March of 1904. The letter is not literary journalism; rather, it points to a book-length unpublished work, When I Was Mary-Anne, a Slavey, which chronicles Franklin’s immersion in domestic service in Sydney and Melbourne for a year.

Roe, in her definitive biography of Franklin that follows the anthology, describes Franklin’s Mary-Anne as a characteristically adventurous episode in Franklin’s life and situates the immersion as a “personal turn-of-the-century social experiment” and “participant investigation” that further opens the literary journalism door, given the form’s relationship to ethnographic practices.2 Roe briefly details Franklin’s time as a domestic servant, laments the resulting manuscript from the Mary-Anne research was not published, then moves on to Franklin’s years in Chicago.3

If Roe is a lighthouse for Franklin’s life, this research places a spotlight on Franklin’s unrecognized literary journalism, especially Mary-Anne, in the context of her performing what Sue Joseph identifies as “gonzo advocacy journalism.” Joseph charts gonzo advocacy from Jack London’s The People of the Abyss (1903), to George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), and then to contemporary authors Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America (2001), and Elisabeth Wynhausen’s Dirt Cheap: Life at the Wrong End of the Job Market (2005). The focus of Joseph’s taxonomy is immersion in poverty, but Franklin’s Mary-Anne joins a lineage of gendered performance of gonzo advocacy that illuminates feminized low-wage labor emerging with Elizabeth Cochrane’s (Nellie Bly), Eleanor Stackhouse’s (Nora Marks) and Elizabeth L. Banks’ immersions in domestic service in the late 19th century. Roe suggests Banks may have inspired Franklin, as Banks had in 1902 released her autobiography that detailed her immersion as a maid in London, first published as the series “In Cap and Apron,” in 1893. In 1914, Swedish journalist Ester Blenda Nordstrom immersed as a maid on a farm to expose the conditions; and in 1935, Ella Baker and Marvel Cooke posed as women for hire in the “Bronx Slave Market” where unemployed women of color gathered for underpaid day labor as servants. In 1950 Cooke returned to the market for the New York Daily Compass, and in 1979 Atlanta Constitution reporter Charlene Smith-Williams worked as a motel maid.4 Early in the 21st century, Ehrenreich, then Wynhausen, “utilized the ethnographic immersion methods” of her predecessors to “‘perform’ as gonzo advocacy journalism,” working in minimum-wage positions. Wynhausen acknowledges Ehrenreich as the inspiration for investigating the Australian experience, and Jan Wong followed suit in Canada for the Globe and Mail series, “Maid for a Month” (2006). Together this lineage of gonzo advocacy performed through a feminized and feminist lens amplifies the inequality women experience in the low-wage service labor of cleaning, maids, and waitressing.

This research affirms Franklin’s place in gonzo advocacy journalism and further recognizes literary journalism as the “submerged half of the … canon” in Franklin’s prolific early writing career, rather than “topical writings.” While Franklin’s published article, “San Francisco: A Fortnight After” (1906), is the most accessible exemplar of Franklin’s little-known literary journalism, Mary-Anne is important for its gonzo advocacy and critique of the myth of equality that resonates today with women employed in low-wage service roles.

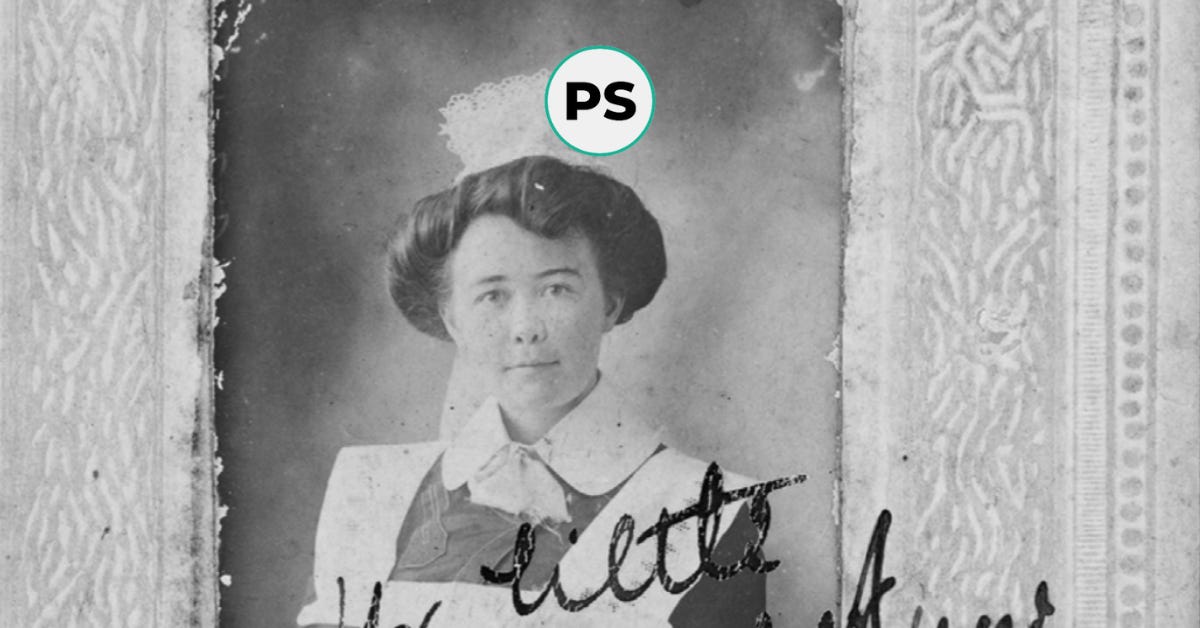

Miles Franklin

Born in 1879, Stella Miles Franklin grew up in rural southern New South Wales, Australia. She sent the manuscript for her debut novel to Australian poet and short-story author, Henry Lawson, who championed it to his London agent, and My Brilliant Career was published in 1901.

Franklin, 21, was hailed as an emerging literary star, but manuscripts for her sequel to My Brilliant Career — “My Career Goes Bung” — and another novel, On the Outside Track, were both rejected.5 Franklin then turned to literary journalism in 1903, immersing as a domestic servant for a year. Franklin left Australia in 1906 to work with Australian expat and feminist Alice Henry in Chicago, editing the journal Life and Labor, produced by the National Women’s Trade Union League of America. Franklin then moved to London, and during World War I joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals as an orderly and cook. After the war, Franklin’s fiction gained prominence again with her 1936 award-winning novel, All That Swagger, and a series of six novels written under the pseudonym Brent of Bin Bin, beginning with Up the Country: A Tale of Early Australian Squattocracy in 1928. Roe describes the series as “The Brent of Bin Bin Saga.”

Upon her death in 1954, Franklin bequeathed the Miles Franklin Literary Award, which remains Australia’s most prestigious literary prize for novelists. Because of this legacy, her literary journalism remains largely unknown.

‘Mary-Anne, a Slavey’

From April of 1903 to April of 1904, Franklin immersed as a domestic servant seeking “literary material,” and throughout the year kept a diary of all her experiences. Some of these are excerpted in the Mary-Anne manuscript and pre-date Franklin’s collected published diaries that begin in 1909, adding to the manuscript’s importance both to literary journalism and epistolary scholarship around Franklin.

Franklin began her “Mary-Anne immersion in Sydney, presenting herself in need of employment. As Nora Marks did in Chicago in 1888 when she investigated domestic service conditions for the Chicago Tribune, Franklin emphasized her country innocence. Bar a few trusted confidants, Franklin told her social and writing circles that she was traveling overseas, and no one in 1903 expected an Instagram post. Franklin initially answered newspaper ads but found the experience fruitless, so turned instead to an employment registry office that placed her as a “General” in a private house in Waverley, near Bondi. There, she encountered a romantic milkman to whom she revealed her emerging feminist views on marriage:

“Do let me talk to you, just a minute.”

“Certainly, if you talk sense, but don’t begin to invite me out at night as I’ve made an inflexible rule to do so with no man.”

“You’ll be an old maid at that rate,” he said.

“There are worse fates than that in matrimony,” I retorted as I scampered off with my jug.

Upon leaving Bondi, Franklin endured a short stint with a difficult employer whom she characterized as caring more for her dogs than her family; then a popular boarding house on the harbor where she worked as a parlor maid, and a politician’s home. She concluded her year working for a society family, a merchant, a doctor, and a country family in Melbourne.

Despite this year of immersive research, plus months writing, “Miles’ manuscript still awaits its publisher.” The Mary-Anne manuscript is now held in the State Library of NSW as part of the voluminous Miles Franklin Papers and comprises two volumes of handwritten “sketches,” but the final draft is missing. Roe writes: “What happened to the completed manuscript is unknown, except for a passing commiseration from Sir Francis Suttor, president of the Legislative Council and a new patron in Sydney, that Mary-Anne ‘did not take on’ with the publishers.” Franklin succeeded in publishing only the short article in 1904 for the Bulletin, “Letter From Melbourne,” describing her year as a servant, and written as she concluded the immersion; a Sydney Morning Herald opinion piece in 1907 in which Franklin reflects upon her “practical experience” in domestic service to argue for better working conditions; and a small, similar article in the Chicago Tribune while she lived in the United States. Then Mary-Anne disappears. Norman Sims reminds: “Literary journalists gamble with their time…. The risks are high. Not every young writer can stake two or three years on a writing project that might turn up snake-eyes.”

Franklin biographer Colin Roderick describes Bulletin literary critic A. G. Stephens as having thought the manuscript’s sketches were better suited to a series in the Sydney Morning Herald, but Roe and Bettison’s companion index of Franklin’s topical writings, many of which were not included in the anthology, do not list any Mary-Anne-related articles for the Herald beyond the 1907 opinion article. Roe mentions that in 1905 Franklin told the editor of the Herald that she’d finished the “servant book,” suggesting there may well have been a conversation about serialization that never eventuated. Roe believes Franklin’s Mary-Anne has enduring value, and implies that publishers’ wariness of Australia’s strict defamation laws contributed to derailing publication of the manuscript in whole or part: “For various reasons, such as length and the sensitivity of the approach (Grandma Lampe characteristically thought it deceitful), it could hardly have been published at the time.” Roe further alludes to one of the reasons for the manuscript of Franklin’s sequel to My Brilliant Career being initially rejected was her penchant for skimming characters too closely from life for a publisher’s comfort.6

Gonzo Advocacy or Stunt Journalism?

From the 19th century to contemporary practice, women literary journalists have been criticized for performing gonzo advocacy that investigates low-wage service labor. Cochrane (Bly), Banks, and Stackhouse (Marks) were known derogatorily as “girl stunt reporters” who practiced participatory immersive research, including domestic service, to prove their worth to publishers, and became a fixture of sensational yellow journalism in the late 19th century. The practice has since been viewed as privileged women slumming for a story who were in turn exploited by commercially driven publishers, or in contemporary iterations for their own profile and profit. Fellow Australian journalist Ellen Fanning was critical of Wynhausen’s immersion working as a waitress, cleaner, and factory worker, arguing that Wynhausen could have anticipated the cushioning effect of the Australian minimum wage “before she headed out of Bondi.” The deliberate mention of the fashionable Sydney beach suburb in which Wynhausen normally lived reiterates Fanning’s critique of Wynhausen’s privilege. Reviewer Monique Rooney counters that Fanning misses Wynhausen’s more subtle illumination of the impact of deregulation on low-wage work security, particularly for women. Likewise, the media historian Randall Sumpter refutes the stunt is entirely sensationalist. Discussing Banks, he argues “this genre in the hands of an experienced practitioner could range beyond the predictable topics and locations, incorporating balanced sources and employing ethics-based decision-making.” His argument aligns with Ted Conover’s view of ethical participatory immersive practices.

Was Franklin an aspiring stunt journalist? She did not have a career in women’s pages to escape, or a commissioning editor to impress. Although Roe suggests that Banks may well have been an inspiration, it seems Franklin’s Mary-Anne is self-conceived outside any external publishing pressure. At the turn of the 20th century, the so-called “servant problem” was discussed at length in the Australian press and the Mary-Anne title of the manuscript popularly referred to a woman working in domestic service.

In a summary of her immersion, “Concerning Maryann,” Franklin writes she was interested in investigating the servant-question debate:

Some people wonder what domestic servants have to complain about. To satisfy my own curiosity on the point, I determined under the name Mary- ann Smith, to follow the calling for 12 months. No one could understand the depth of the silent feud between mistress and maid without, in their own person, testing the matter.

Franklin’s rationale and resulting manuscript align with Robert Alexander’s view that “Gonzo [journalism] is a fiercely political style of reportage with a powerful commitment to what … we call socio-political intervention.” For Franklin, both the novelistic style of literary journalism and the sociopolitical interventionist aims were instinctive. Franklin’s Mary-Anne fits Joseph’s view of gonzo advocacy journalism and Orwell’s aim to make political writing an art form. Joseph argues that London, Orwell, Ehrenreich, and Wynhausen all “engage in a form of Gonzo ethnography, ultimately critiquing issues of poverty, social divide, and a certain voicelessness of social subsets in order to bring them into mainstream consciousness, with an often self-deprecating, satirical, but definitely intense, lilt and performance.”

On the latter point, Franklin’s Mary-Anne is self-deprecating and has a “satirical but definitely intense” lilt; Franklin gives parody names to the homes and boarding houses where she immerses, such as “Geebung Villa,” and critiques the absurdity of the middle-class Australian household mistress: “The running of this midget establishment is like playing cubby house….” Rather than a short-lived stunt, Franklin is determined to experience the domestic servants’ “lived reality” that supplies “new lines of evidence, context and attempts at understanding disadvantage in relation to the dominant culture and power structures.”

Franklin exhibits “ethics-based decision making” in her disclosure to fellow maids that she was immersing in domestic service for book research purposes, although she stopped short of telling them that she was the author of My Brilliant Career. Reflecting the aims of performing gonzo advocacy, the maids that Franklin confided in urged her to give voice to their realities of domestic service. Franklin also writes that, “I deliberately told several of my mistresses I was really ‘maryanning’ for ink writing purposes … they kindly let pass the trifling dementia…,” and she disclosed that she was a writer to guests from the United States, whom she befriended while working at a boarding house.

That Franklin was ambitious for publication in book form places her more securely in gonzo advocacy, given that Joseph emphasizes book-length literary journalism in aligning the work of London, Orwell, Ehrenreich, and Wynhausen. Matthew Ricketson argues there are six qualities evident in book-length literary journalism, beginning with the obvious: writing about “actual events and people living in the world, and concerns the issues of the day,” and extensive, time-consuming research. Franklin uses pseudonyms but underlines the actuality of her narrative in “Concerning Maryann,” which is bolstered by Roe citing the locations and employers of her domestic service posts. Franklin writes:

I am not so colossally conceited as to think in one 12-month, or in one book compiled from the diary I carefully kept during that period, I could give a recipe for the satisfactory adjustment … [I] state the facts that I collected, in a straight way regardless of consequences….

Ricketson’s next three elements continue tenets familiar to literary journalism, in that they take a narrative approach, employ a range of authorial voices, and explore the underlying meaning of the event or issue. In Franklin’s Mary-Anne, narrative structure is evident in the scene setting, dialogue, literary devices, and independent sketches that work as chronological chapters. The underlying meaning is recognized through Franklin’s performing gonzo advocacy, and her authorial voice of satirical outrage and vulnerability radiate throughout multiple points of view. The existing manuscript draft begins with Franklin posing as Mary-Anne in the first person — “I am ill with fear of failure” — that sets the participatory tone. From the fourth sketch, Franklin changes to limited third person to become the characters, “Mary-Anne,” then “Jane.” Analyzing Norman Mailer’s similar third-person, limited point of view in Armies of the Night, James E. Breslin posits the technique as “inflating the self,” which seems Franklin’s intention in Mary-Anne. Arguably the first-person sketches are more successful for their intimacy and authenticity, but without Franklin’s final directions or final manuscript it is difficult to ascertain which point of view she ultimately preferred, if any. Perhaps she kept them both.

Whatever the point-of-view decision, Franklin’s voice has parallels with John Stanley James (“The Vagabond”), who, Willa McDonald argues, concentrated “on powerlessness rather than poverty as the driving subject matter.” Franklin’s voice gives insight into brittle domestic sphere power relations in post-colonial Australia that are supported by structural inequalities:

The biggest blot on the household arrangements was the maids were brutally overworked but the blame of this rests on society at large rather than upon the individual. This Mrs. Bordinghaus was not violating any civil laws in regard to her maids — she was doing the usual thing.

Yet Franklin’s voice also retains a self-awareness of her privilege. She recognizes that she can, and does, take refuge with wealthy friends whereas her fellow “Mary-Annes” cannot. After a particularly difficult day, Franklin observes:

Oh, my blistered hand and jangled nerves! What of the girls who have no home awaiting their return when they fail in these battles? Who, if they wanted to, save enough for board while they searched for another engagement would be compelled to endure weeks of this Billings-gated slavery!

The final element identified by Ricketson is the impact that gonzo advocacy inevitably accrues upon publication. While a series rather than a book, it is worth noting that Banks’ “In Cap and Apron” sparked a debate in letters to editors about the servant question in London. Ehrenreich received letters from low-wage workers, one of which read: “I appreciate the fact that you were willing to experience first hand what many of us live with day to day…. You witnessed the ‘pariah’ syndrome the working poor experience daily.” Although Mary-Anne was never published, Franklin wrote about Mary-Anne in the Bulletin’s “Letter From Melbourne” and was interviewed by the national women’s magazine The New Idea, known now simply as New Idea. The work in progress was mentioned in the feminist journal the Australian Woman’s Sphere. The full impact of Franklin’s Mary-Anne may be yet to come.

Ricketson’s qualities of book-length journalism do not specify empathy. However, John Hartsock identifies empathy as a necessary quality in narrative literary journalism. Hartsock elaborates, arguing that discernment between literary journalism and sensationalism can be found in literary journalism’s “attempt to narrow the distance between the subjectivity of the journalist and reader on the one hand and an objectified world on the other.” Lack of empathy is a main consideration of Hartsock’s reservations about Jack London’s The People of the Abyss, primarily: “[H]is inability to understand empathetically the subjectivities of the Other….” But empathy, it seems, is in the eye of the literary journalism scholar. Unlike Hartsock, Joseph sees empathy in London’s text and argues it is all the more powerful for its “savage look at ignored social destitution and deprivation within mere kilometers of untold wealth and entitlement.”

Franklin empathetically immerses herself in the “inferior” experience, so her advocacy is strengthened by its presence. She does not hold herself apart from the maids but respects the domestic servants she works alongside as colleagues and conspirators. Yet she retains perspective, such that she is able observe herself retreating into the silence of servitude:

With the exception of necessary remarks I am utterly silent, for this intangible something has gripped my feelings in a hand of ice and so frozen my individuality that only the mechanical part of me is in evidence. By doing some necessary work in another man’s home instead of in my own, I have become an inferior creature….

Gonzo Advocacy and Bodily Sacrifice

In her study of girl stunt reporters, Jean Marie Lutes argues that their performative journalism meant that they endured “bodily sacrifice,” and Pablo Calvi critiques a similar physicality in the contemporary writing of literary journalist Gabriela Weiner. Calvi observes: “Gonzo puts the entire perceptual body — and not just the disembodied eye — into the flow of the world.” It follows that bodily sacrifice is a defining characteristic of gonzo advocacy in Franklin’s Mary-Anne. Franklin emphasizes her physical appearance in appraisals by prospective mistresses, employment registry agents, and experienced servants. Franklin is repeatedly called too sensitive and slight for the demands of domestic service and admonished to be tougher by her peers lest she be worked to death. Tellingly, Franklin’s friend, the feminist Rose Scott, warns Franklin to protect herself from bodily sacrifice upon learning she is working as a servant:

My dearest Stella, I was glad to hear from you — but dear one — do you only get an hour on Saturday? Have you no arrangement for an afternoon and evening out? A day a month? Or any outings? Because if so you will hurt the girls you want to help — they will think if you do not want times out, why should other girls! Think of this point — for the sake of others, you must not be a slave…. I do not say this out of selfishness and because I want you—

Little time off was soon the least of Franklin’s bodily sacrifice. In the first sketch of the manuscript, written while working at Waverley, Franklin details how she suffered a near blinding injury when the gas stove blew up in her face, only to have to continue working in a haze of blistering skin and pain:

That stove! That infernal stove! … [T]he oven was filled with gas, which, when I opened the door, rushed out, and igniting by the lighted cooking jets on top enveloped me in flames…. The extent of my injuries were the loss of my eyelashes, the charring of my eyebrows and a band of front hair, my face was mostly in blister and my fingers painfully burned. The pain was so intense I had difficulty in suppressing a scream but instead had to fry the eggs and bacon warm potatoes and make the toast.

Franklin must have confided in Scott or other trusted confidants, as a small news article appeared in 1903 reporting her facial injuries as a result of a gas explosion, but it does not say the accident happened because Franklin was working as a servant. At the conclusion of the year, she mentions her “Gretchen like locks” and scalp were still scarred from the burns.

Her physical injuries flow into an undercurrent of harassment that Lutes identifies as a hazard and bodily sacrifice. As a maid, Franklin negotiates flirtatious men, which she treats as humorous, but the undercurrent is evident. In a diary excerpt, she writes of a maid’s necessary qualities with the survival of the power relations of harassment in mind: “She must be sufficiently comely to be smart, yet not so attractive as to win any stray admiration from the male members of the family she serves.”

Franklin’s Literary Journalism: After ‘Mary-Anne’

In the drought of her novels and the Mary-Anne manuscript rejection, Franklin turned to shorter works of literary journalism to earn a writing income. Roe estimates that, between 1905 and 1906, Franklin contributed over 30 articles to the Sydney Morning Herald and Daily Telegraph, as well as periodicals such as the New Idea and Steele’s Magazine. Of these, the forensic Roe leaves a trail of literary journalism breadcrumbs in Franklin’s biography that suggest other literary journalism articles not collected in the “topical writings” anthology. Roe highlights that Franklin participated in “A Mountain Cattle Muster” in the Australian Snowy Mountains, and wrote another work of travel literary journalism, “A Kiandra Holiday,” “both described in such a way that the reader wishes they had been there.”

The strength of the “Muster” article is Franklin’s reportage of the Australian landscape and her capturing of the characters of the bush. Describing, in the second installment of the two-article series, the horse ride through the rugged high country, Franklin writes: “the rattle of the horses’ hoofs among the hard, water-worn boulders was enough to make one shudder, as it seemed as if they must be bruised and split to pieces…. In the same article, Franklin characterizes the lead stockman as “triumphantly driving the steers before him with the crack of a 15-foot stockwhip, and holding a heavy pipe between a set of false teeth, where it had remained through all the action.”

Franklin wrote these articles and other pieces for the Herald under the pseudonym “Vernacular.” She would display a liking for pseudonyms throughout her career.

The following year, and tellingly under her own name, Franklin also wrote for the Herald, “San Francisco: A Fortnight After,” which chronicles the Great Earthquake damage she witnessed upon arriving in the city. “San Francisco” can be repositioned historically as a companion piece of literary journalism to Jack London’s far better known story, “The Story of an Eyewitness,” which chronicles the city in the hours after the disaster. Far more than simply “topical,” Franklin’s evocative, finely observed scenes show a ruined city revealing itself in the dawn and struggling to survive its new reality. Franklin writes:

Shortly after midnight on Monday, April 20th, the Golden Gate was entered, and the liner cast anchor down stream at about 2 a.m. … Right ahead gleamed acres of city night eyes, giving the impression that there was a great deal of the city yet standing. … As the daylight strengthened it looked like a series of vast rubbish tips cut out in squares where the streets had been, and from it all arose the odour of a great burning.

Franklin observes: “The first landmark to catch the eye of the traveler was the tower of the Ferry Building, with its flag-pole bent and out of plumb, and its big clock pointing to a quarter-past 5, the fatal hour on the morning of April 18th, when the earthquake occurred.” She sees tangles of pipes in apartment buildings, and notices silence where there should be “the hum and rattle of street cars.” Always a horsewoman, Franklin takes special note of the exhausted horses replacing suspended steam and electric transport: “Some of the gaunt and sweated creatures ran for 48 hours without rest.” “San Francisco” also exhibits Franklin’s perennial eye on equality as she describes the disaster reducing class distinctions to rubble.

Upon arriving in Chicago, Franklin continued freelancing for Australian newspapers and periodicals. Her article, “Letter From Chicago,” shows her eye for social observation: “It was a traveler’s party, and after we had eaten our ice creams (it is impossible to conceive of the Americans conducting anything from a prize fight to a mission service without the aid of ice cream)….” Her writing for Life and Labor in the years after falls more into reports and feature-style profiles but is informed by her previous year-long immersive research for Mary-Anne. Although Franklin seems to have shelved the Mary-Anne manuscript, Roe notes that she surveyed employment agencies as research for her Chicago Tribune article, “No Dignity in Domestic Service.” According to Roe, there is a school exercise book cover filed among her unpublished plays with a penciled heading, “The Misdemeanours of Mary Anne,” suggesting she rewrote it for an unrealized theater production while living in Chicago. There is also an undated, unfinished manuscript, Untitled Novel re Mary, a Servant Girl, that carries similarities to “When I Was Mary-Anne, a Slavey.” Later, the main first-person character in Franklin’s satirical drawing room mystery novel, Bring the Monkey, poses as a maid to attend a society party, evoking Franklin’s real-life Mary-Anne.

In 1915, Franklin moved to London. To support the war effort, she served as a volunteer orderly and cook in the Balkans, where she wrote the work of literary journalism, “Active Service Socks.” She describes the camp and again exhibits her ability to capture place: “The winds rushing down the valleys between the ancient, denuded hills, carrying heavy rains, which make camp existence a soggy thing and cold….”

Conclusion

Franklin remains revered in Australia as a novelist. Yet this reputation over-shadows her unrecognized contribution to early 20th-century literary journalism. Revisiting Franklin’s non-fiction writing in the early period of her writing career reframes her relevant work as literary journalism, and Franklin as a literary journalist, rather than a fiction writer dabbling in occasional “topical” writings.

“San Francisco, A Fortnight After” is the most accessible of Franklin’s literary journalism. It is a companion piece to Jack London’s “The Story of an Eyewitness” and, more widely, literary journalism writing on natural disasters. However, the unpublished book-length Mary-Anne is arguably a more important work, as it establishes her as a contributor to literary journalism’s tradition of performing gonzo advocacy, which Joseph traces from London and Orwell to Ehrenreich and Wynhausen.

Franklin takes her place in a more gendered gonzo advocacy that examines low-wage service labor through a feminized lens that amplifies the inequality women experience in these roles and challenges myths of meritocracy. The 19th-century works of Cochrane (Bly), Stackhouse (Marks), and Banks are tangled with the historical tags of stunt-girl reporting that hides their gonzo advocacy. Rather than also be dismissed as an aspiring stunt-girl reporter, Franklin meets Ricketson’s requirements for book-length literary journalism. Her work’s contribution is strengthened by Hartsock’s additional view that literary journalism is characterized by empathy, and empathy radiates throughout Mary-Anne. Franklin’s work enlivens the debate about gonzo advocacy by stunt-girl reporters and is a historical counterpoint to both early 20th century and more recent immersions in service by women literary journalists.

In the contemporary labor market, the rise in women’s employment in Australia is dominated by low-wage caring roles, such as childcare. According to the NWLC, in the U.S., “women represent nearly two-thirds of the workforce in low-paid jobs,” many of which are cleaning and waitressing. More than a century after her immersion, Franklin’s performance of gonzo advocacy in her exploration of the “servant question” endures.

Follow our Continuing Education section for discussions with academics concerning narrative reporting in the classroom and the state of media in colleges and universities; syllabi, reading lists, and coursework to continue your own education; and coverage of other topics in the study of journalism.

The Postscript

Additional content and context, added to everything we do.

Collaborate: Partnership Credit

A version of this story was first published in the December 2020 issue of LJS, a peer-reviewed journal from the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies, a multi-disciplinary learned society whose essential purpose is the encouragement and improvement of scholarly research and education in literary journalism (or literary reportage).

Meet: About the Author

Kerrie Davies is a lecturer at the University of New South Wales’ School of Arts and Media in Sydney, Australia, where she teaches journalism. A former journalist, she is the author of A Wife’s Heart (University of Queensland Press, 2017) — a biography of Australian poet Henry Lawson’s wife, Bertha Lawson, and memoir on single parenting — and a contributing researcher to the Colonial Australian Narrative Journalism database.

Read: Footnotes

Miles Franklin arrived in San Francisco two days after the earthquake, contrary to the Sydney Morning Herald’s headline.

See also Ted Conover’s extensive relationship with ethnography, detailed in Immersion: A Writer’s Guide to Going Deep.

Jill Roe’s hefty biography, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, is the authoritative study of Franklin’s life.

“I Was a Part of the Bronx Slave Market” appeared in the Compass throughout January of 1950.

Both were later revised extensively and published: Originally called The End of My Career, My Career Goes Bung: Purporting to Be the Autobiography of Sybylla Penelope Melvyn appeared in 1946, and “On the Outside Track” became the basis of Cockatoos: A Story of Youth and Exodists, published in 1954 under Franklin’s pseudonym, “Brent of Bin Bin.”

Colin Roderick, in Miles Franklin: Her Brilliant Career, also mentions defamation concerns around Miles Franklin’s rejected sequel to My Brilliant Career.