'What Inna Namea Christ Is This': The Origins of Tom Wolfe's Journalistic Voice

Famous not only for his idiosyncratic, exuberant use of punctuation but for what one commentator called his "wake-the-dead" prose style, Tom Wolfe has one of the most distinctive journalistic voices.

“That’s good thinking there, Cool Breeze.” I was hooked the moment I read these words way back in 1982. I was a cadet journalist on The Age in Melbourne, Australia, when a respected senior colleague said if you want to know about the LSD scene in the sixties, if you want to see what can be done with journalism, read Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

It’s not journalism, it’s a book, I thought, but I bought a copy and read that opening sentence. It just drops the reader right into the middle of the San Francisco heads scene, poking fun at Cool Breeze’s paranoia about the law while he is garishly dressed and riding in the back of a pick-up truck. “Don’t rouse the bastids. Lie low.”

Closing the book 370 pages later, I had had a mind-expanding experience of my own. That journalism did not have to stop at hard news — “A family of four has been killed in a car collision…” — was the first revelation. Wolfe’s book opened a door in my mind; I glimpsed a house at once larger and designed in ways I’d never imagined before. What I really loved, though, raised on a diet of newspaper columns, bland, formal, and parental, was how Wolfe, who died at age 88, in 2018, talked directly to me as a reader. And he wrote with a frankness unheard of in newspapers — “I pick it up and walk out of the office part, out onto the concrete apron, where the Credit Card elite are tanking up [their cars with petrol] and stretching their legs and tweezing their undershorts out of the aging waxy folds of their scrota.” Once seen, that’s an image I’ve never quite been able to unsee.

Ask most readers their first impression of Wolfe’s journalism and they will mention his highly individual voice, his “wake-the-dead prose style,” as David Price put it in an aptly vivid phrase for a Nieman Storyboard piece. Reading more of Wolfe’s work over the years evidenced other things — his fascination with trends, his zest for ideas, his obsession with status, his eye for the satirical, his use of a range of narrative methods, his interest in journalism’s history, and, finally, his politics, which I have to say I found unappealing. But what has stayed with me is the distinctiveness of his journalistic voice, and I have often wondered where it came from.

Unlike many journalists, Wolfe has always been happy to discuss his own work. In “Like a Novel,” one section of the long essay, “The New Journalism,” that introduces the landmark anthology he co-edited with E.W. Johnson, that bears the same title, The New Journalism, Wolfe writes that he would try anything to capture the reader’s attention when, early in his career, he began writing for a new Sunday supplement of the New York Herald Tribune. The status of this and other supplements was then “well below” that of newspapers: “Readers felt no guilt whatsoever about laying them aside, throwing them away or not looking at them at all. I never felt the slightest hesitation about trying any device that might conceivably grab the reader a few seconds longer. I tried to yell right in his ear: Stick around!”

It was hard not to stick around, given the audacity and inventiveness of devices Wolfe employed to keep readers’ attention. He opened a piece about Las Vegas for Esquire magazine in February of 1964 with the word “hernia” written 57 times, mostly in lowercase but sometimes as “HERNia,” before asking the question that must have been on every reader’s mind: “What is all this hernia hernia stuff?” The answer is that if you say the word hernia quickly, repeatedly, it sounds like the spruiking of craps table dealers in the casinos. Other journalists might have noted that the hubbub in a casino sounds like the word hernia, but few would make what is actually a slight observation the focus of their opening paragraph, and none other than Wolfe would have magnified it into the playfully intriguing, attention-seeking device it is. Nor is the wordplay gratuitous; the question “What is all this hernia hernia stuff?” is actually asked by a man named Raymond who exemplifies the impact Las Vegas’ surreal, never-closed atmosphere has on the senses. Wolfe reports that Raymond has been awake for 60 hours, continually gambling, eating, drinking, and taking drugs: His senses were “at a high pitch of excitation, the only trouble being that he was going off his nut.”

As the repeated use of the word hernia was unmissable, so was Wolfe’s idiosyncratic approach to punctuation, which included abundant use of exclamation points, ellipses, parentheses, and dashes, partly as a way of breaking up gray slabs of text on a magazine page and partly because, as he told George Plimpton, editor of the Paris Review, in a 1989 interview, he was emulating the novelist Eugene Zamiatin (whose name is sometimes spelled Zamyatin): “In We, Zamiatin constantly breaks off a thought in mid-sentence with a dash. He’s trying to imitate the habits of actual thought, assuming, quite correctly, that we don’t think in whole sentences.” Wolfe uses ellipses sometimes to leave an implication dangling and sometimes for emphasis. For instance, in “The New Journalism,” he writes that those who don’t believe journalism is important should take up other work, like becoming a “noise abatement surveyor….” In the next paragraph, extolling the pleasures of saturation reporting, he writes “‘Come in, world,’ since you only want … all of it….” Sometimes onomatopoeia is deployed, as in his description of Baby Jane Holzer in a 1965 article, “The Girl of the Year,” whose brush-on eyelashes sit atop “huge black decal eyes” that “opened — swock! — like umbrellas.” At other times, flouting George Orwell’s dictum, “Never use a long word when a short one will do,” Wolfe chooses rarefied words, such as “gadrooned,” as he did in his article “Radical Chic” to describe the decorative motif on the cheese platters being served the Black Panthers because, he says, it gave the piece “bite” and because it was less important the reader might be unaware of the word, as they could be “flattered to have an unusual word thrust upon them.”

As the love of wordplay suggests, for Wolfe there is a strong performative element in his journalistic voice. In “The New Journalism,” he derides the virtue of understatement in journalism as “that pale beige tone” which is accompanied by “a pedestrian mind, a phlegmatic spirit, [and] a faded personality.” He, of course, exhibits the polar opposite, for better and for worse. The essay overflows with the journalistic equivalent of soaring rock star lead guitar solos, everything from denunciations of newspaper columnists’ “tubercular blue” prose to fond evocations of desperate competitiveness in the feature writers’ “odd and tiny grotto,” and from amazement at Gay Talese’s storytelling feats (“I’m telling you, Ump, that’s a spitball he’s throwing…”) to heralding the arrival of the “accursed Low Rent rabble” with their “damnable new form” that was set to dethrone the Novel as “literature’s main event.” Sometimes, Wolfe extends his performance by adopting what he calls a “downstage voice,” mimicking the tone and vernacular of, say, Junior Johnson, the stock car racer from Ingle Hollow, North Carolina, or, in The Right Stuff, of test pilot Chuck Yeager.

What characterizes Wolfe’s journalistic voice, then, are: exaggeration, energy, inventiveness, playfulness, a keen sense of performance, and a wickedly satiric eye. His voice has won glowing praise and sharp detractors. William McKeen, author of the one of only two book-length studies of Wolfe’s work, calls him the Great Emancipator of Journalism for his contribution to expanding the possibilities of non-fiction writing. Norman Sims, author of True Stories: A Century of Literary Journalism, recalls how Wolfe’s voice astonished and captured him as a student in the 1960s, not least because Wolfe appeared to have access to interior lives of the people he reported on. John Hartsock, author of a respected history of literary journalism in the United States, notes that what “most attracted readers to Wolfe and created a critical furor around him were his linguistic pyrotechnics that seemed to pose a taunt to advocates of standard English usage.” On the other hand, James Wood, the literary critic, has frequently lambasted Wolfe’s work, especially his fiction, but also mocked his “screeching italics and arrow-showers of exclamation points, and ellipses like hysterical Morse code.” Whatever Wolfe’s critics might say, his journalistic voice is instantly recognizable, widely copied, and has been so influential over the past four decades that it is hard to recapture its sheer freshness when Wolfe burst onto the scene back in the mid-1960s.

A Look at the Beginnings

Despite Wolfe’s standing as a leading figure in the loose group known as the New Journalists and the attention from scholars his work has attracted, little work has been done on the origins of his journalistic voice. What attention there has been has accepted Wolfe’s own version of how he discovered his journalistic voice, partly because Wolfe is as good at telling stories about himself as he is at telling others’, partly because he has told it so often in interviews, and partly because to date much of the primary source material has been unavailable.1

Wolfe laid down what Tom Junod called “his own origin story, his own creation myth” in the introduction to his first collection of journalistic pieces, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. By the time the book was published in 1965, Wolfe was 35 years old and had been in journalism for nearly a decade. He described his growing frustration with the totem newspaper’s way of reporting the lives of anyone outside officialdom, which is to say, “the totem story usually makes what is known as ‘gentle fun’ of this.” Wolfe was fascinated by the minutiae of people’s lives and the meaning they invested in their interests, such as hot rod and custom cars. Taking an assignment from Esquire magazine, he trekked to California and collected a welter of material. After returning to New York, he found himself blocked for a week, whereupon his editor, Byron Dobell, with a photo of an exotic car already laid out and deadline looming, told him to type up his notes and Dobell would knock them into shape. Wolfe takes up the story:

So about 8 o’clock that night I started typing the notes out in the form of a memorandum that began, “Dear Byron.” I started typing away, starting right with the first time I saw any custom cars in California. I just started recording it all, and inside of a couple of hours, typing along like a madman, I could tell that something was beginning to happen. By midnight this memorandum to Byron was 20 pages long and I was still typing like a maniac. About 2 a.m. or something like that I turned on WABC, a radio station that plays rock and roll music all night long, and got a little more manic. I wrapped up the memorandum about 6:15 a.m., and by this time it was 49 pages long. I took it over to Esquire as soon as they opened up, about 9:30 a.m. About 4 p.m. I got a call from Byron Dobell. He told me they were striking out the “Dear Byron” at the top of the memorandum and running the rest of it in the magazine.

It is a story that is at once neatly shaped — the only editorial change required was deleting “Dear Byron” — and evocative of Romantic-era myths surrounding writers with a capital W. Wolfe recycles it in his introductory essay in The New Journalism. Other than noting Wolfe’s penchant for self-promotion, most of those who have written about Wolfe’s work have repeated this story uncritically, including McKeen; Brian Ragen, author of Tom Wolfe: A Critical Companion; and Marc Weingarten, who, in From Hipsters to Gonzo: How New Journalism Rewrote the World, added little more than that Dobell had cut Wolfe’s repeated use of the phrase “for Christ sakes” and written the “throat-clearing headline.”

New knowledge about the origins of Wolfe’s voice became available in 2014 when a rich source of primary material, Wolfe’s papers, was deposited in the New York Public Library. There are eight audio files and 219 boxes of documents. The bulk cover the period from 1960 to 1998, comprising, among other things: correspondence with family, friends, colleagues, and sources; drafts of stories, clippings, research files, reporter’s notebooks, photographs, drawings, and miscellany, such as invitations to events, tickets, and invoices from tailors in Savile Row, London, for various bespoke items Wolfe had ordered.

Initially, the archive was not digitized and put online, so the materials were available for use only in the library. Staff in the library’s manuscripts and archives division are discreet about the identity of researchers, but at least one is known because he wrote about the papers in Vanity Fair. Michael Lewis, author of Moneyball, The Blind Side, and The Big Short, is probably as big a name in journalism today as Wolfe was in earlier decades. In a lengthy piece headlined “The White Stuff” (or, in the online edition, “How Tom Wolfe Became … Tom Wolfe”), published in November of 2015, Lewis sieves the mass of material to find out how the man whose work first inspired him to write did what he did. It is a fascinating piece, which would be expected from a journalist of Lewis’ caliber, but equally intriguing was how Lewis has, by and large, reinforced Wolfe’s “origin story” and how he underplayed the impact of an important event in Wolfe’s life, namely that he initially failed his Ph.D. thesis and has rarely, if ever, discussed that publicly. There is ample material in the archive that, first, suggests a longer, subtler, and, yes, less dramatic origin story for Wolfe’s journalistic voice; and, second, a connection between the revised origin story and the gap in how Wolfe has represented his time as a postgraduate student at Yale University.

With only limited time to examine the Wolfe papers during a visit to New York in 2016, this research draws on nine of the 219 boxes, mostly those covering his childhood and early writings, but there is more material that shows just how early Wolfe was exhibiting signs that were to become his signature during the 1960s. His penchant for $10 words surfaced early. In one story written during high school at St. Christopher’s in Richmond, Virginia, when stock car racers came to town, he wrote about the “revered, calorific drivers,” later describing how one of them drove with “an even wilder, more sulphurous zeal than ever before.” His teacher questioned the appropriateness of this usage but graded the story 83 percent. Fellow students also noticed his vocabulary: In an issue of Washington and Lee University’s monthly magazine, the Southern Collegian, an article by Wolfe carried the following precede: “Verboze T.K. Wolfe redeems himself with this sterling sports recapitulation of the Class of ’51.” It is verbose; Wolfe drops the words “nabobs” and “verdant” into the opening paragraph.

Wolfe wrote a column called “In the Bullpen” for St. Christopher’s school newspaper, the Pine Needle, in 1946-47, which is filled equally with original phrase-making and sporting clichés. More important, one column is cast in the form of a “scene” inside a gym where a football coach is talking to his players before the game. Headlined “Carnage, Inc.,” the piece opens with “Scene: A quaint, docile gymnasium tucked in among the pines of a peaceful community.” It soon becomes apparent the scene is imaginary; the coach is trying to calm his bloodthirsty charges, one of whom has a giant plaster cast on his arm that flattens a section of wall that he has inadvertently brushed. The interaction between coach and players is recorded as dialogue, complete with stage directions:

Coach: Boys, boys, I’m beginning to doubt your intentions in Saturday’s game.

DeVanport (cleaning his fingernails with a three-foot ice pick): Now, now, Coach, don’t worry — everything we do is for the honor of Alma Mater.

Welterflood (sharpening his cleats): And besides, who knows, a few scalps might do wonders for the study hall.

Coach (taking a bottle of aspirin tablets out of his pocket): This skull practice is getting me down. Come, little monsters, out we go to the playing field.

Yes, the scene is imagined and adolescent, but what is striking in light of Wolfe’s famous listing of narrative devices in “The New Journalism,” is how he deployed two of them — scenes and dialogue — decades beforehand as a teenager for a school newspaper column. His response to the world around him, even in the narrow confines of student journalism, is to construct and dramatize what he sees.

At university and then at graduate school while studying for a doctorate, Wolfe tried his hand at fiction, poetry, and journalism. One short story entitled “Goddam Frozen Chosen” and written in 1955-56 has signs of Wolfe’s hyperkinetic approach to sentence structure. Set in Seoul during the Korean War, the story aims to capture the chaos and boredom of military life and portrays U.S. soldiers stumbling around naively in brothels or drunk while on duty:

They are laughing so hard, so pointlessly, the words come out only between various wheezes, sighs, gasps, moans, shrieks, hiccoughs, all manner of inscrutable convulsions and suspirations: “My god” — gasp, wheeze, shriek, moan, sigh, whistle “another god—” — snuffle, wretch, pule, slobber, roar — “goddamn frozen Chosen [hotel] — DON’T LET HER GET AWAY!” — blam! — a plug of elm tree explodes out amidst the essential elements, blood, fire and urine. Only Lt. Woods can hit the trees, however. Lt. Glassock is so drunk, he can barely get the rifle out the window, besides that this swivel chair in here is … a … real … mother! Blam! — wah- whwahwahwahwahwahwah, gasp, shriek, moan, sigh, oh scrogging frozen Chosen.

And so, it goes on. Wolfe, perhaps inspired by Zamiatin, whose work he read while at Yale, aims to imbue his story with a linguistic style that mirrors the chaos of the soldiers’ experience, but he does not yet have the control to make this passage seem much more than a word salad. Overall, the story is hard to follow and not especially engaging.

It was in his doctoral work in American studies at Yale University, though, that Wolfe made his first sustained attempt to marry fictional techniques with non-fiction material. For his dissertation topic, he investigated how the Communist Party of the United States during the 1930s and early 1940s set up, controlled, and manipulated the League of American Writers, an organization whose 14,000 members included some of the nation’s most respected authors. The topic, and Wolfe’s argument that members of America’s literary establishment were susceptible to communist control, prefigures Wolfe’s continuing preoccupations — and his battles — with liberal establishment leaders in literature, art, and architecture, especially over his works “Radical Chic,” The Painted Word, and From Bauhaus to Our House.

Alongside conventional methods of academic research and writing, Wolfe presented his findings in what looks like an early version of the New Journalism. A draft chapter entitled “Beaux Arts on the Barricades” opens with a brief narrative reconstruction of a North American artist leading “a band of guerrillas in an unsuccessful machine-gun raid on the Cocoayan, Mexico, home of Leon Trotsky,” before moving to what readers of Wolfe’s later work would recognize as his popular sociological style: “Legions of less famous artists were clogging the stale corridors and second-story flats of lower Manhattan where, grimly, vicariously, with veins popping out on their necks, they spent the decade arguing those issues so intimate to them all.”

After the awkward use of an archaic word, “shatterpating” (meaning to shatter, or scatter your brain), Wolfe cranks up his rhetorical armory to dismiss the relevance or legacy of socially realistic art and writing of the 1930s: “What happened to all those starveling workers, lardiform politicians, billy-happy policemen, eroded landscapes, hookwormy sharecroppers, humble-shouldered mestizos, unbound proletarian Prometheuses, and poor old hemp-collared colored men which filled up such vast wall and canvas space barely 15 years ago?” In style and sentiment this passage would not look at all out of place in Wolfe’s so-called breakthrough Esquire piece about custom cars.

In a draft of another section of the thesis, Wolfe reconstructs a session of the House Committee on Un-American Activities from 1947, complete with stage directions for an exchange met with “applause and boos” between the chair and a writer:

The scene was actually a good deal more uproarious than the transcript of the hearing reveals. Thomas [the chair] was shouting at Lawson [the writer], hailing police officers, and battering his desk top. Lawson was holding the witness table in chancery before him, crouching like a Greco-Roman wrestler behind it, and shouting into his microphone. Press photographers were ricocheting off one another at close quarters and setting off flash bulb explosions. Three hundred public spectators there in the caucus room of the old House Office Building were whooping, hollering, hissing, whistling, laughing, stomping on the floor — like any Friday night boxing crowd at the Uline Arena 18 blocks away.

The examiners of the thesis did not exactly warm to Wolfe’s approach. Michael Lewis thinks that is because they were a bunch of stuffed shirts.

Maybe they were, but that may be only half the story. A fidelity to factual accuracy is a bedrock of both long-form journalism, or literary journalism, as it is also known, and scholarly research. As Norman Sims has noted, many literary journalists research their topics as intensively as a doctoral student.2 University faculty who have both professional journalism and scholarly research experience are able to see many continuities as points of contrast between the two activities, especially in research and the practice of long-form journalism, or literary journalism. If that is the continuity, then yes, the contrast is in the prose. For anyone with literary aspirations, the form of the conventional Ph.D. dissertation can be frustratingly rigid.

It is easy to see why Wolfe would have chafed against it. But if Wolfe had simply engaged in hijinks for his Ph.D. dissertation, that is not what most concerned the examiners. They all actually believed that he wrote “very skilfully.” Further, they found his argument convincing: “The literati were indeed manipulated by the communists,” wrote the American studies graduate supervisor, David Potter, on May 19th, 1956, summarizing the three examiners’ reports in a letter to Wolfe. What the examiners also found, though, and it is worth quoting at length, was that the thesis was:

Not objective but was consistently slanted to disparage the writers under consideration and to present them in a bad light even when the evidence did not warrant this; second, that you had relied on a one-factor explanation, which, in the opinion of the readers, may be valid but has not been proved and probably cannot be proved as a single operative factor. There was a third criticism which I had not anticipated, and which seems to me more damaging than either of the other two: this was the criticism that you misused your sources, giving incorrect quotations, misstating evidence, etc. All three readers checked various sources (a routine duty of readers) and all three made this criticism.

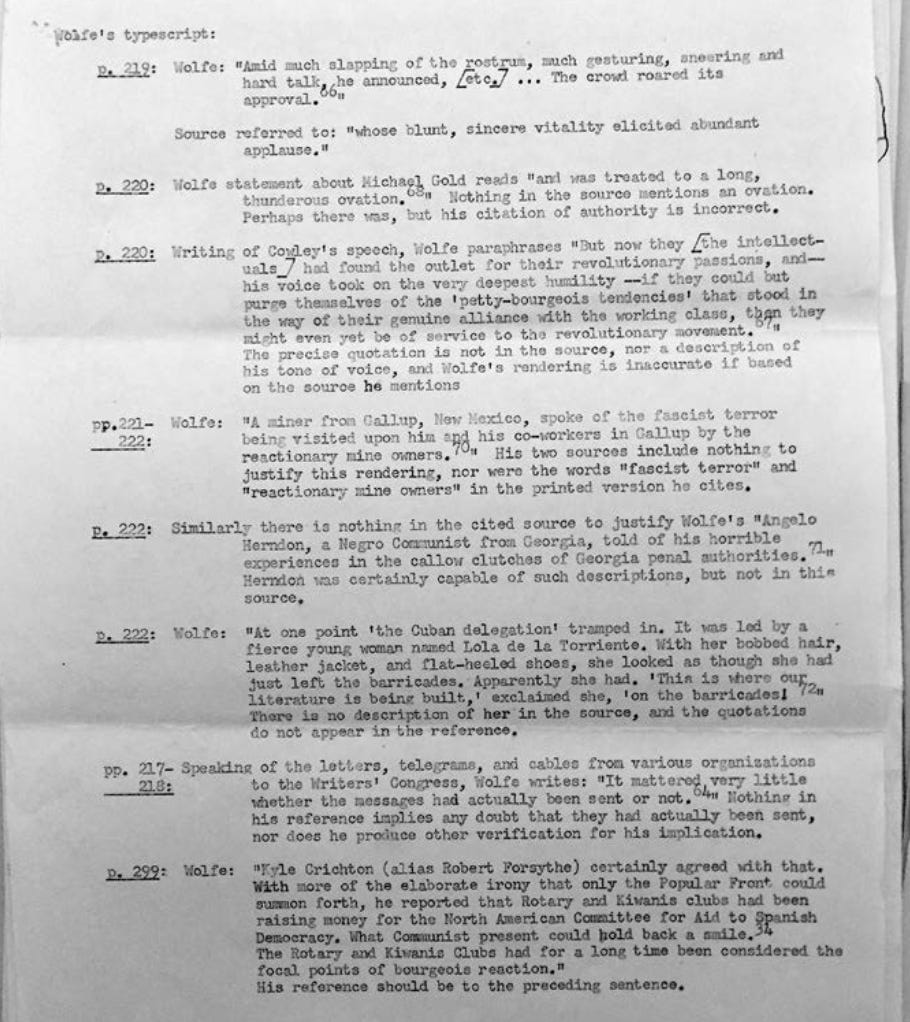

They had indeed; the three examiners’ reports make scarifying reading. One examiner wrote that Wolfe’s polemical rhetoric colors every page. “His use of pejorative and biased qualifiers and terminology seems at times to be little better than what he properly critiques on the part of others.” Another provided two pages of notes unfavorably comparing Wolfe’s descriptions with the primary source material. For example, Wolfe wrote: “At one point ‘the Cuban delegation’ tramped in. It was led by a fierce young woman named Lola de la Torriente. With her bobbed hair, leather jacket, and flat-heeled shoes, she looked as though she had just left the barricades. Apparently she had. ‘This is where our literature is being built,’ exclaimed she, ‘on the barricades!’” There was no description of her in the sources and the quotations did not appear in the references, the examiner found.

The reports presciently lay out evidence of later criticism — and praise — of Wolfe’s work. He does, of course, write “very skilfully.” He had an uncanny ability to pluck out an essential kernel about an issue or trend: identifying the self-expressive impulse behind the creators of custom cars, or the quasi-religious nature of the Merry Pranksters’ acid experiments, or the pretentiousness of many liberals’ identification with the Black Panthers, or the special bonds forged among the early astronauts in The Right Stuff.

Wolfe does tend to try to stretch his brilliant insights into an entire argument, though. Throughout his work, status is portrayed as not only the most important, but almost as the only source of motivation in people’s lives. That is, he relies too heavily on a “one factor explanation.” James Wood has consistently criticized Wolfe’s fiction, and one of his main points applies equally to Wolfe’s journalism: “The kind of ‘realism’ called for by Wolfe, and by writers like Wolfe, is always realism about society and never realism about human emotions, motives, and secrecies. To be realistic about feeling is to acknowledge that we may feel several things at once, that we massively waver.”

Finally, Wolfe has been criticized for his inaccuracies and for his misuse or misrepresenting of sources, notoriously over his two 1965 articles about The New Yorker, but also by eminent early literary journalist John Hersey and by various scholars. These criticisms were spurred in part at least by Wolfe’s ringing assertion that the New Journalism sat atop a bedrock of accurate reporting — “All this actually happened,” as he famously put it.

The essential elements not only of Wolfe’s journalistic voice, but of his overall journalistic and intellectual approach are already in place by the mid-1950s while he was still in graduate school. The importance of the Ph.D. thesis episode, then, is, first, that it undercuts the tidiness of Wolfe’s presentation of his own “origin story” and, second, that Wolfe’s response to Yale prefigured a series of fights he has had with people in the worlds of journalism, literature, art, and architecture, which reaches its apotheosis in his unedifying brawl with those he dubbed “My three stooges” — John Irving, Norman Mailer, and John Updike. On the first point, we can take Wolfe at his word that on the night he wrote the “Dear Byron” memo he experienced a sense of creative release when he broke through his writer’s block, but a read of the custom car article again today shows it actually does read, in many ways, like a very long memo. It is certainly ambitious for a magazine piece of 1963 in outlining a historically informed argument about the culture of custom car enthusiasts, but most of the piece stays close to the conventions of magazine journalism at the time. There is surprisingly little evidence of the fictional techniques that had so electrified Wolfe the year before when he read Gay Talese’s brilliantly evocative profile of former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis and exclaimed, “What inna namea christ is this.”

Wolfe’s use of fictional techniques is actually more evident in “The Marvelous Mouth,” a profile of Cassius Clay, as he was then known, that was published in Esquire in October of 1963, a month before “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.” It is not clear, however, whether “The Marvelous Mouth,” was written before or after the custom car piece. Certainly, “The Marvelous Mouth” lead has the kind of journalistic conceit that Wolfe made famous with his “Las Vegas!!!!” piece, mentioned earlier, and reprints dialogue between Clay and his entourage. It also has a scene, more vivid than any in the custom car article, in which the dazzling boxer who was to become heavyweight champion the following year is forcibly reminded of his roots in racist Louisville, Kentucky.

A middle-aged white southerner shoves a train ticket receipt in front of Clay, saying, “In a voice you could mulch the hollyhocks with: ‘Here you are, boy, put your name right there’.” Asked if he has a pen for the autograph, the man says he doesn’t but is sure some of Clay’s people would. Clay has been staring at the piece of paper without looking up. After about 10 seconds, his face still turned down, he says: “Man, there’s one thing you gotta learn. You don’t ever come around and ask a man for an autograph if you ain’t got no pen.” Why would Wolfe not choose this piece for his “origin story,” especially as by 1965 when he told the story in the introduction for his first collection of articles, Clay had become heavyweight champion, defeating the seemingly invincible Sonny Liston, and shedding his “slave name” to become known as Muhammad Ali? Perhaps that had something to do with it; Ali was an extraordinarily popular (and unpopular) figure whose fame would have overshadowed that of the just-emerging young journalist. Ali was also an extraordinary individual whose approach to everything from race to self-publicizing to boxing challenged conventions and U.S. society and was less susceptible to Wolfe’s sociological approach. Perhaps, too, Wolfe knew this. In a 1966 interview with Vogue on the back of his first collection of journalism, Wolfe told Elaine Dundy that he never felt he had connected with Ali and admits that “I missed the important story about him: that he was getting involved with the Black Muslims at the time I was seeing him.” That he was still insisting on calling Ali “Clay” in 1966, two years after the boxer had changed his name, may offer a clue as to why he missed that particular story.

To understand the second point of importance requires knowing Wolfe’s response to the examiners’ reports on his Ph.D. thesis. And before that, requires knowing that Wolfe was brought up in a genteel, well-to-do family in Richmond, Virginia. Even well into his thirties he would address his letters home to “Dear Mother and Daddy” and sign them “Tommy.” The tone and vocabulary of the letters, indeed, vary little from adolescence right through to when he was making his name as a journalist in New York. His letters home, many of which are in the archive, are unfailingly polite, solicitous, and bland. They carry so few traces of Wolfe’s public voice that a reader begins to wonder what on Earth his parents made of his journalism. Writing to them on November 4th, 1963, that Las Vegas is “a monument to all that is grossest and flashiest in modern American taste,” is just about the strongest opinion he expresses in letters to his parents. It is a long way from “Hernia, hernia, hernia.”

In the archive’s holdings of letters to friends, Wolfe’s language is more colloquial and forthright, as might be expected, but his letter to “Chaz,” on June 9th, 1956, almost three weeks after he received the letter from Yale, fairly jumps off the page:

These stupid fucks have turned down namely my dissertation, meaning I will have to stay here about a month longer to delete all the offensive passages and retype the sumitch. They called my brilliant manuscript “journalistic” and “reactionary,” which means that I must go through with a blue pencil and strike out all the laughs and anti-Red passages and slip in a little liberal merde, so to speak, just to sweeten it. I’ll discuss with you how stupid all these stupid fucks are when I see you.

Wolfe is enraged; he doesn’t see, or want to see, what, if any, were the merits of the examiners’ findings, but he did revise the thesis and it duly passed so that he was graduated in 1957. From that point on, there appears to be no time when Wolfe publicly discusses the humiliating experience of initially failing his dissertation submission. In “The New Journalism,” he compares graduate school to being imprisoned. So “morbid” and “poisonous” was the atmosphere that it defied the many student inmates who promised to satirize it in a novel, Wolfe writes. Similarly, in the many interviews Wolfe has given over the years, a generous selection of which have been gathered by Dorothy Scura in Conversations With Tom Wolfe, he has little positive to say about the Yale experience other than it was where he was introduced to the work of social theorist Max Weber. In one interview, with Toby Thompson for Vanity Fair in 1987, when Wolfe’s first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, was published, Wolfe again recalled graduate school as “tedium of an exquisite sort,” while a friend of his, the novelist Bill Hoffman, was quoted saying, “The professors didn’t know what to make of him…. He was supposed to present scholarly papers, and he would write them in this fireworks style of his and just drive them crazy.”

It is true that some find graduate school a stultifying experience, just as it is true that others find it liberating or energizing. What is curious is that Wolfe has not publicly discussed the criticism made of his Ph.D. dissertation even though he clearly disputed it. It is one of the few episodes in his life where he has refrained from a public fight; usually he relishes them. Wolfe’s father held a Ph.D. from Cornell University. In his letters home that are held in the archive, Wolfe does not mention what happened at Yale other than to say the Ph.D. was a “horrible experience.” When Michael Lewis asks Wolfe in 2015 what he thinks about initially failing the thesis he submitted for the Ph.D., Wolfe says he harbors no ill will toward his examiners and thinks, in retrospect, that “Yale was really important for me.” It was 60 years later but it appears to be at least a tacit acknowledgement that the Yale professors may have had a point.

A Different Perspective on the Origins

The search for the origins of Wolfe’s journalistic voice in his papers at the New York Public Library sheds light on both how it developed and how Wolfe chose to represent it, and himself, in later years. Wolfe was celebrated initially for the zest and flair with which he plunged into 1960s U.S. culture, but what the material in the archive makes clear is how developed his ideas and style were by the time he found a congenial medium — the Herald Tribune’s Sunday supplement and magazines — and creative editors such as Byron Dobell and Harold Hayes at Esquire and Clay Felker at New York (which originated as the Herald Tribune’s Sunday supplement). There is evidence to suggest Wolfe had long had a penchant for the $10 word, which he deployed with an inventiveness that belies or at least qualifies Orwell’s dictum; he loved to dramatize events he wrote about and impersonate voices in print; and, as a result, he would understandably feel constrained by the rigid conventions of academic writing and, later, news reporting. As one colleague said of Wolfe’s time at the Washington Post between 1959 and 1962: “Every time he turned out something fresh and original, he found himself assigned to a story on sewerage in Prince Georges County.”

Nothing in the library’s archives dims that memory of the first rush of excitement at reading Wolfe’s work. His journalistic voice remains highly original even though a reading of George C. Foster’s journalism via Thomas Connery’s Journalism and Realism shows that other journalists experimented with capturing the rhythms of speech in newspapers as long ago as the mid- 19th century. The archive does, though, diminish the sense that his voice was first and foremost a response to what he described as “the whole crazed obscene uproarious Mammon-faced drug-soaked mau-mau lust-oozing” scene in the 1960s United States. Wolfe’s journalistic voice is actually a good deal more constructed than was apparent to a young journalist, for better and for worse. That is clearer now, to someone who has since then read a lot more literary journalism and studied it closely. As an older academic, too, I can appreciate the critique of Wolfe’s work by those crusty old examiners at Yale, even if describing his writing as “very skilful” is correct but utterly juiceless. It would be as if Wolfe had simply written in that passage in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test that some drivers had got out of their cars and filled their petrol tanks. That’s accurate but not exactly something you see in your mind’s eye — let alone something you can’t unsee.

Follow our Continuing Education section for discussions with academics concerning narrative reporting in the classroom and the state of media in colleges and universities; syllabi, reading lists, and coursework to continue your own education; and coverage of other topics in the study of journalism.

The Postscript

Additional content and context, added to everything we do.

Collaborate: Partnership Credit

A version of this story was first published in the Fall 2018 issue of LJS, a peer-reviewed journal from the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies, a multi-disciplinary learned society whose essential purpose is the encouragement and improvement of scholarly research and education in literary journalism (or literary reportage).

Meet: About the Author

Matthew Ricketson is an academic and journalist. He has worked on staff for newspapers and magazines in Australia and led journalism programs at three universities, including Deakin University, where he is a professor of communication. He is the author of three books and editor of two.

Read: Footnotes

The “origin story” is mentioned in at least four of the interviews collected in Conversations With Tom Wolfe by Dorothy Scura.

A personal observation, if my experience is anything to go by: My working life has been split 40/60 percent between journalism and academia. I started in newspapers, moved to teaching journalism in a university, went back to newspapers and then returned to the academy in 2009. Unlike most career academics, I did my Ph.D. later in life, graduating in 2010. Thus, also unlike many who have spent their entire careers in either journalism or academia, my experience has enabled me to see these continuities as points of contrast between the two activities, especially in the main area I both research and practice — long-form journalism, or literary journalism.